Over the years I have been asked many times to recommend a tuning recipe for ensemble keyboards, or else to tune them myself. Choosing a tuning system has always been problematic—the symmetrical sixth-comma temperaments that are so prevalent these days (Vallotti, Young, etc) have never been very satisfying, for several reasons. Firstly, they aren't historical (both were published long after the Baroque era); secondly they are boring (a lot of the keys sound the same); and thirdly they create a number of ensemble problems, making it difficult for orchestra members to lock in to a resonance and pitch center.

Over the years I have been asked many times to recommend a tuning recipe for ensemble keyboards, or else to tune them myself. Choosing a tuning system has always been problematic—the symmetrical sixth-comma temperaments that are so prevalent these days (Vallotti, Young, etc) have never been very satisfying, for several reasons. Firstly, they aren't historical (both were published long after the Baroque era); secondly they are boring (a lot of the keys sound the same); and thirdly they create a number of ensemble problems, making it difficult for orchestra members to lock in to a resonance and pitch center.

The ubiquitous "Vallotti" temperament, published in 1779 by the Padua composer, theorist and organist Francesco Antonio Vallotti, has become the default tuning for many of today's Baroque musicians who feel obliged to play in some kind of unequal temperament. It is simple, consisting of six adjacent pure fifths and six adjacent fifths that are tempered by 1/6 comma, and it is therefore easy to remember. It is circular, meaning that in principle it can be used in all keys. And Baroque string players like the fact that their open string intervals are all tempered the same amount.

But the Vallotti tuning, in my experience, has for decades been a persistent source of intonation problems for Baroque instrumental ensembles, creating uncertainties for the bass instruments that find their way into the rest of the group. Essentially, what tends to happen is that the flat side of the tuning ends up being the highest notes in the scale, so that notes like F, Bb and Eb seem to float and nobody in the group knows quite where they are supposed to be; since these notes often serve as the roots of chords in a lot of Baroque music one can be left with a distinctly queasy sensation—consider, for example, the first two Eb-major chords of "He Was Despised"—how often do they sound in tune?

Some ensembles have attempted to improve on Vallotti by using the "Young #1" tuning, another theoretical temperament, described by the English physician and polymath Thomas Young in 1799. While slightly less problematic, Young retains the aggressively high Eb, Bb and F pitches that make ensemble tuning difficult in flat keys and make chords such as F# major unusable.

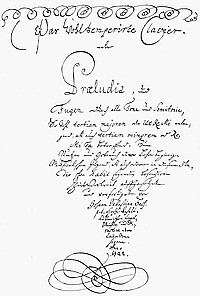

For a while when people asked about temperaments I would give up and say "just tune it equal" (which after all IS a historical tuning, described in the early 17th century and favored by Rameau among others) but this wasn't totally satisfactory either, and provoked more than one raised eyebrow from the authenticity police. Then I became aware of the work of Bradley Lehman, who makes a very convincing case that Sebastian Bach's preferred keyboard tuning was one that he apparently describes in a diagram on the cover of Das Wohltemperirte Clavier. Click here for more information about Lehman and his work on this subject. While still a sixth-comma tuning Bach/Lehman distributes the pure fifths somewhat differently from a symmetrical system like Vallotti, and addresses some of its most thorny problems. In ensembles where Bach/Lehman has been used, tuning has been much less problematic in my experience, and resonances easier to find.

We should remember, though, that Bach's diagram was associated with a volume of solo keyboard music, a tuning intended to be listened to rather than played with. For ensembles, and especially for orchestras of mixed strings and winds, I believe it is possible to improve on Bach/Lehman in one significant way—by making F-C and Bb-F pure intervals, one can make the often-majestic music written in those keys sound very resonant indeed, and also make ensemble tuning in flat keys in general more predictable for bass players.

Further research revealed that a slightly tamer version of this tuning was actually published in 1724 by Johann Georg Neidhardt, Kapellmeister at Königsberg in Prussia, this retains the pure fifths from F-C and Bb-F but less bright in the sharp tonalities, making it especially useful for trumpet music in D, for example. It is known variously today as "Neidhardt 1" or "Neidhardt 3" although at the time he called it the "Dorf" or village temperament—interestingly Neidhardt recommended a different tuning for large cities, and 12th-comma meantone (i.e. equal temperament!) for court use.

In any event here is my recipe, along with approximate comparisons with Bach/Lehman, Neidhardt Dorf, Vallotti, and Young #1, written in whole cents deviation from equal temperament for ease of use with an electronic tuner. If you are tuning by ear, similar results can be achieved by making sure that C-F and F-Bb are tuned pure, and distributing the other enharmonic fifths ad libitum.

| C | G | D | A | E | B | F# | C# | G# | Eb | Bb | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hammer | +6 | +4 | +2 | 0 | -2 | 0 | +2 | +2 | +2 | +2 | +2 | +4 |

| Bach/Lehman | +6 | +4 | +2 | 0 | -2 | 0 | +2 | +4 | +4 | +4 | +4 | +8 |

| Neidhardt "Dorf" | +6 | +4 | +2 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -2 | 0 | 0 | +2 | +2 | +4 |

| Vallotti | +6 | +4 | +2 | 0 | -2 | -4 | -2 | 0 | +2 | +4 | +6 | +8 |

| Young #1 | +6 | +4 | +2 | 0 | -2 | -2 | -2 | 0 | +2 | +4 | +6 | +6 |

Note that the sixth-comma tempered intervals between the "open string" notes are identical in all five tunings. Bach/Lehman places pure fifths from E-B and B-F#, creating a distinctly brighter character as you migrate toward sharp keys; it also places a mild wolf fifth from Bb to F—interesting indeed, and it sounds great in solo keyboard music from Bach to Chopin, but is perhaps too gnarly for an orchestra. My revision, with even twelfth-comma fifths between all the enharmonic notes, is easier for instrumentalists to cope with, and as noted above, creates wonderfully resonant fifths in F and Bb. Neidhardt goes a step further, by tempering E-B and B-F# slightly the G-major, D-major and A-major sonorities are rendered less bright. Choice of temperament is, of course, a matter of personal taste, but I would propose that choosing Bach/Lehman, Neidhardt Dorf, or my formula instead of Vallotti or Young will contribute substantially to tuning stability in an instrumental ensemble while retaining the character and variety of a non-equal temperament.

I have used this formula for music by Bach, Telemann, Handel, Rameau, Mozart, and many other eighteenth-century composers. It works! Try it sometime and send me your comments. Remember that the idea is to tune the keyboard to the temperament (since a temperament is by definition a set of decisions about which intervals the keyboard will play out of tune, and by how much) and then to try to play intervals in musical context that sound in tune which may not always be the same as matching the treble notes of the keyboard. Also bear in mind that some repertoire (especially French and early-Baroque music) permits the use of more irregular or non-circulating temperaments, allowing for more interesting sonorities.

A version of this article appeared in the Fall 2010 issue of Early Music America

For more discussion of the perils of tuning Baroque orchestras, see also

A Modest Proposal.

A discussion of Neidhardt's tuning philosophy and variety of temperaments, part of a very useful site on historical tuning by the piano-maker Paul Poletti can be found here